Vol. II, No. 11

Friday, October 24, 2025.

St. Paul, MN

A RIGHT HONORABLE Soldier

By Mrs. Jane Hadley.

IN WHICH Henry finds an opportunity to be safely seen and Charley lets herself boss everyone around.

XXI.

Outside Columbia, Kentucky

Friday, January 10, 1862

THE next day, the sick were sent back to Lebanon in the wagons. They laid over for two days, taking some much deserved rest after building the bridge, but it was cramped and damp because the rain kept coming. By Friday, the cold had cut to Henry’s bones, and he drank extra coffee trying to banish it. It was no wonder so many fellows were getting sick.

“It’s the measles,” Jacob was saying as he and Henry trudged across the camp to fetch rations for the rest of the squad. “Steer clear of that hospital tent. The fellows in the Kentucky regiment are falling like flies.”

“We’ve worked so hard for so long to see battle. I’ll be damned if I get sick and miss it.”

“Tell that to Captain Noah,” Jacob agreed. “He’s in that wagon train heading back to Lebanon.”

“Is he on leave, then?” Henry turned toward Jacob in interest.

“Yeah, either Lieutenant Woodbury or Thomas is gonna get promoted to captain.”

Henry’s eyes lit up. “Do you think Osborn will get picked up for first sergeant, if Nelson is promoted to lieutenant?”

“I know he’s been angling for it. I guess we’ll find out.”

“I keep telling Charley to go for Corporal,” Henry said. He steeled himself to be cautious with his pronouns and added, “This might be his chance.”

Jacob gave him a sideways glance.

“What?”

“Nothing.”

“No, you gave me a look. What?”

“Oh, I dunno, Schaefer. Do you really think Smith would make a good corporal? Seems like he’d be a tyrant, if you ask me.”

Henry frowned. “I don’t think so.”

“Well, you wouldn’t, being his bosom friend and all.”

Henry felt his face get hot. “I don’t think he’d play favorites.”

“No, he wouldn’t play favorites. He’d push us all to the brink, except you.”

“I really think you’re being dramatic.”

Jacob rolled his eyes. Then, he huffed a laugh. “It would be funny, though, to see Smith try to keep us all on a tight leash under Webster, who just wants to tuck us all into bed and tell us a bedtime story.”

Henry laughed too. “That would drive him nuts. Wait—if Osborn is promoted, does Webster decide who gets corporal?”

“I suppose he would.”

“Hm. I’d better remind Charley to make his case to Webster, then, too.”

“Oh, I see how it is.”

“What? No you don’t.”

“I do. You’re encouraging him. What’s your game, Schaef? Looking for privileges?”

“No,” Henry retorted reflexively. He already had all the privileges he could ever want when it came to Charley. Except privacy. “I just think he’d be good at it, is all.” Jacob gave him a sour look. “I’m serious! Smith doesn’t lose his temper unless the top brass is already doing something profoundly stupid. Wouldn’t you like to have someone with a thimbleful of common sense moving up the ranks? Someone who doesn’t just sit quietly and fawn over the fellows in charge?”

“Men like that never get promoted,” Jacob sniffed.

“They do if the men listen to them,” Henry insisted. “If Charley is given the chance, I think we’d better support him. A little goes a long way with him.”

“What does that mean?”

Henry blinked. “I just mean that … if you give him one measly compliment, he’ll fight to the death for you. It doesn’t take much to earn his loyalty, and he fights hard for people.”

Jacob gave him a flat look. “I think that might just be you, Schaef. We haven’t seen battle yet, but I’d bet fifty dollars that that boy will take a bullet for you. I wouldn’t make the same bet for any of the rest of us.”

Henry stilled. He couldn’t think about that. No, he couldn’t consider that scenario at all, so he grabbed at his indignation like a life preserver. Jacob was several paces ahead of him by the time he got hold of it. “You’re wrong. Smith would do that for all of us. You’re just sore because you had to buy your blanket back from him.”

“Should I not be?”

“You dropped it in the ditch! If it weren’t for Smith, you would have no blanket at all and probably be on the sick wagon back to Lebanon.”

Jacob frowned. Henry seized his advantage. “Smith isn’t nurturing like Webster, I’ll give you that. But he takes care of people. He’d make a damn good corporal, or any other rank they’d be smart enough to give him.”

Jacob sighed. “Damn, Schaef. You got it bad.”

Henry blanched. “I don’t know what you’re talking about.”

“It’s fine. Everyone knows. You follow Smith around like a puppy dog.” Jacob didn’t appear at all concerned. “It’s okay. Lots of young men love their best friends. It’s how we learn how to love, isn’t it?”

Henry’s mouth dropped open.

“I don’t know what you’re all embarrassed about. I loved Hower for a time, before you ever came to the farm back in Faribault.” Jacob shrugged. Henry suspected that the way he had loved Hower was not at all comparable to the way he loved Charley. But Karl had said something similar, so perhaps Henry was simply naive.1

Regardless, he was grateful when they arrived at the commissary tent and he had a moment of distraction to wrangle a parcel of rations in his arms and think.

“I can carry it, if you want,” Jacob offered reflexively.

“No, I got it,” Henry replied. Their squad was issued but the one parcel, so unless they wanted to carry it between them, it was one or the other. “It’s really not that heavy.”

They started back toward the tent.

“You know, maybe I am letting my own resentment color my opinion of Smith,” Jacob said idly as they walked. “I suppose when it comes down to his actions, he’s an honorable sort of fellow. He’s just such a blowhard, it’s hard to see past it.”

“I know,” Henry replied. “He’s all bark, though.” And sometimes bite. But only in the best way. “I, um. I guess you’re right. I do love him.” God, it felt so good to say. He’d been wanting to shout it from the rooftops, but he’d been terrified of compromising Charley. He thought he’d have to keep his distance. But if he could speak of love with Jacob, even if it was presumed platonic, well … it was a comfort. “I never expected to.”

“I know. You thought he was a spy.”

“Shut up.”

Jacob laughed. “Turns out you’re just a glutton for punishment.”

“I am not. I was just wrong. Very wrong. He’s smart and passionate and entirely uncompromising. I admire him so much.”

“Aw,” Jacob said, chuffing him in the shoulder. “I knew you had it bad.”

Henry swam in the comfort of being seen.

“I just think,” Jacob began slowly, “that you ought to be careful.”

“I know, it’s unseemly. Krüger already looks like he wants to rain hellfire down on us whenever he sees us.”

“Not that,” Jacob rolled his eyes, as if Krüger’s propriety was as inconsequential as worrying about French-Russo relations. “I mean, make sure Smith is above board. He’s very determined in his thinking. I’m sure it’s easy to get swept along. But he’s not morally consistent.”

“What do you mean?”

“I mean that damned Sterling House affair! I know we’re at war, Schaef, and fellows have needs, but brothels are the quickest path to syphilitic insanity. That bunk can ruin your whole life.”

Henry paused. It was a tell and he knew it, but he was already doing it before he could think to stop.

“Unless he was lying…” Jacob said, looking back at Henry under a raised eyebrow.

Henry winced. Jacob’s other eyebrow went up to.

“Oh,” he said. A slight blush crept over his cheeks too. “I suppose kisses are not outside the affection of bosom friends,” he added quickly, not meeting Henry’s eyes. “I’m sure it’s none of my business if you wanted a little privacy.”

Henry’s mouth dropped open, and then an embarrassingly high laugh came out of his throat unbidden. “Did you do that with Hower, then?”

Jacob looked scandalized. “Of course not! Not that he didn’t try. He was all, ‘Come on, Jacob. I’ll teach you how.’ But he had nasty breath back then. I guess his mother never taught him to brush his teeth, which is really no excuse because I didn’t have one to begin with and I still have all my teeth. I loved him, but not that much. It was all bluster anyway. He was just angling for practice for himself. I really don’t think that lunkhead can back up any of his boasts.”

“He loves yellow-jacket novels,” Henry agreed.

“Yeah, I think he fancies himself some sort of gothic rake.”

Henry snorted.

“It was short-lived anyway. I was on my own for the first time, and I was so damn lonely, I just attached to the first person who noticed me. Soon as I got the attention of girls, I didn’t need him so much anymore. That’s usually the way of it.”

Henry stayed silent. Maybe that was what Charley was so afraid of. That Henry would meet a girl and forget about her. But that was the thing. Charley was both the bosom friend and the enigmatic girl. She was more than an infatuation or a youthful loneliness displaced. She was everything Henry had never even known he wanted.

“I suppose it’ll be a long time before any of us are able to meet any girls, though,” Jacob said, more like thinking out loud than anything else.

“Do you miss her? Your wife, I mean?”

“I knew it was going to be torture,” Jacob replied, kicking at the ground. “But it’s so much worse than I imagined. There’s no letters, Henry. I write her every day, and I never get anything back. I keep telling myself it’s the mail, it’s delayed or held up somewhere outside of Louisville, but what if she’s forgotten about me? What if she met someone else, someone who is actually there. I did her a nasty turn, marrying her then marching out.”

“No you didn’t,” Henry replied, shifting the parcel to one hip. “You gave her everything you could, given what you’d already promised to Lincoln.”

“Do you ever wish you didn’t enlist? No, don’t answer that. Of course you don’t. You’ve got your bosom friend in your arms every night. Sometimes I wish she could have followed the camp or … or dressed up in trousers so she could be with me. I know, it’s crazy. She never would have anyway. She’s too correct to follow an army camp or do laundry for the troops. And it wouldn’t have worked anyway because they sent all the camp followers away in Lebanon. I don’t know, I’m rambling.”2

“You just miss her,” Henry said, using the arm he’d freed up to squeeze Jacob’s shoulder and ignoring the way his heart was racing. “You should miss her. You love her. I mean, it’d be a bad sign if you didn’t.”

“I know. It’s just unbearable.” Jacob wrinkled his nose, then laughed. “Maybe I can attach myself to you and Smith. Just snuggle up on the other side, make a little Smith sandwich.”

Henry glowered.

“Oh my God! Look at you, so jealous.” Jacob slapped his knee. “Nevermind. I wouldn’t dare get between you and your Confederate spy.”

“Don’t say that! What if someone heard!”

“That’s right, your boy wants a promotion. Apologies,” Jacob teased. “Don’t let him aim too high, though. He gets promoted enough times, you won’t see him anymore.”

⸻

After the midday meal, Company K was called together on the makeshift parade ground. The rain had turned to sleet in the cold and the ground was more a swamp, the boys’ boots all sinking into the cloying mud as they turned their attention to Lieutenant Woodbury.

“Soldiers, attention!” Woodbury shouted. Henry noticed that the men seemed to stand taller for him than they had for Captain Noah, though he suspected that was because Woodbury had done much of their beginning drills at Fort Snelling and had no compunction using a cane to correct them.3 “Captain Noah is still ill, but despite what you may have heard, he is still here with us in camp and has not been sent back to Lebanon on sick furlough. He is on the mend and will be back in ranks with us again soon.”

Henry could see Charley’s shoulders slump slightly in front of him.

“This afternoon, you’ll receive orders to prepare the wagons for an early departure in the morning. See your sergeants for further instructions. Sergeant Osborn’s squad, see Lieutenant Thomas. The rest of you, fall out!”

Henry exchanged a curious glance with Robinson as Williamson asked, “Are we in trouble?”

Osborn’s mustache curled up at the corners. “I don’t think so. Come on!”

Charley fell in by Henry’s side as they trudged through the mud to Lieutenant Thomas.

“So much for a power shift,” she muttered, shoving a palm across her nose.

“Yeah, I guess Captain Noah’s eager to keep hold of his position,” Henry replied. “Is your nose cold again?”

“Yes, dammit.”

“Do you want me to warm it up?”

Charley cast him an alarmed look. “No. Don’t touch my nose.”

They scrambled into the best ranks they could muster given the terrain as Sergeant Osborn gave a salute and said, “Squad Seven, sir, reporting for duty.”

“Sergeant Osborn, soldiers,” Lieutenant Thomas greeted with his hands behind his back. He seemed more poised than Henry was used to seeing. Usually, Thomas was in a constant snit trying to get the privates to make him look good in front of Captain Noah and the Colonel. “You’ve been selected to conduct an advance guard this afternoon.”4

“Sir!” Sergeant Osborn responded. Henry couldn’t see his face, but he could tell he was fighting a grin.

“Looks like Sarg’s brownnosing paid off,” Robinson said to Henry out the side of his mouth.

“Shh!”

“You’ll pair your squad off and go out about 20 rods in advance of the company, which should be about 80 rods in advance of the regiment. Your mission is to scout the route ahead and determine the location of any enemy forces in our path in season to prevent a surprise. Do not engage the enemy. Do not fire unless fired upon. If you are fired upon, retreat to the regiment and inform command immediately. Do you understand your orders?”

“Yes sir,” Sergeant Osborn confirmed, then glanced back at the squad. Webster took the invitation.

“Sir, are we to understand the enemy is within 20 rods?” he asked.

Lieutenant Thomas’s countenance was usually exasperated, but this time, it was more guarded somehow. “Perhaps. That’s what we need you to find out.”

Henry looked at Robinson with some alarm.

“Reports place them within ten miles, so it’s unlikely they’re that close, but we need to check and find out. Sergeant Osborn, your squad has been dependable on the march. I look forward to your report.”

“Sir, yes sir,” Osborn confirmed and the whole squad saluted with him.

They walked tall back to the tent to gather their knapsacks and materials.

“Make sure to bring everything, boys,” Sergeant Osborn said. “If we are engaged, we might not have a chance to return before the camp is struck and we march on.”

Henry could feel the tent hum with excitement. Hower could barely hold in a grin, and Charley had this expression on her face that was both grim and eager. It was rather chilling. Henry shoved his things into his knapsack and checked his haversack to make sure it was filled with rations.

“Does everyone have a full complement of ammo?” Charley asked, checking her own cartridge box.

Henry looked in his box and said, “Yup.”

A chorus of confirmations rang around the tent as the others checked theirs as well. Henry smiled at Charley, then glanced at Osborn who was looking at Charley consideringly. Webster didn’t appear to have noticed anything at all—he was too busy checking his cartridge box as directed.

The squad emerged from the tent and headed south and east toward the Cumberland River. The rain misted over their faces, the clouds gloaming the light and making it feel almost like it was dusk, especially under the cover of trees. When they reached the edge of the picket line, Osborn turned and paired them off.

“I have selected these pairs intentionally, and they’re not your bunkies, so no complaints, you understand?” the Sergeant preempted. Henry exchanged a glance with Charley, whose expression darkened. Her eyes sort of smouldered as her mouth tightened into a line, and Henry felt his stomach flip to be regarded so possessively. “I’ll have Robinson and Williamson, Hower and Krüger, Webster and Smith, and Schaefer, you’ll be with me.”

Henry frowned. Why pair Charley with Webster? Unless he was letting the Corporal take stock of Charley’s skills. “Oh, okay.”

He wasn’t sure why he felt so discomfited as he watched Charley and Webster lope off to the north east, heading into the cover of a pine grove.

“Come on, Schaefer, let’s go,” Osborn said. Henry followed him due east, down a grassy hill snaked with a split-rail fence.

Henry and his sergeant travelled silently for a while. The mud was less troubling in grassy areas, but it slopped anywhere the ground was bare. Henry’s feet were already damp, and it took less than an hour for his boots to become saturated. The wetter the weather, the colder it felt.

Osborn led the way around trees. They moved as quietly as they could, staying behind cover and peering around trees when they reached open areas to survey for enemy scouts. Henry was wound tight at first, imagining greybacks lurking around every shrub. Imagining Charley off in the woods with Webster, who was a lovely man in many respects, but without the fighting spirit that Charley had. He couldn’t help but fear that if they met hostiles, Charley would defend them both and Henry couldn’t bear the risk that posed. He quickly squashed these imaginings, filling his mind instead with a Heine poem he’d memorized at Turner Hall. “Die Lorelai” just made him think of Charley, though.5

After an hour, Henry adjusted to the rhythm of their scouting. Moving methodically, looking carefully for any movement or disruption. The mud was thick and would have shown footprints readily, so it was heartening in a way to be taken by surprise when stepping on a misleading mud slick. He couldn’t help but wonder if the other fellows were having a better time, chatting together quietly as they surveyed their assigned tract. He supposed Osborn was right to split him and Charley apart. Henry was pretty confident that he would not be as attentive were she there to distract him.

Around three o’clock in the afternoon, Osborn gestured for Henry to join him under the canopy of a pine tree and break for water. Henry took a swig out of his canteen, looking around the wood.

“I understand Smith is looking for a promotion,” Osborn said.

Henry glanced over at him. “Yeah. I think he’d be good for it.”

“I do too,” Osborn agreed. “I put him with Webster in hopes he can win him over. If he can manage some diplomacy, it’ll go a long way.”

“Do you think there will be a shift in command soon?” Henry asked. “What with Captain Noah being sick and all?”

“There’s lots of rumors,” Osborn said. “I don’t know what will happen. Getting this assignment is a good sign, though, for me and for anyone else looking for advancement.”

Henry nodded and thought for a moment.

“Sir, do you think Charley could move up?”

“What, do you mean higher than an NCO?”

“Yeah.”

Osborn tilted his head consideringly. “I suppose he could, if he could make the right impression. Why, are you worried about getting left behind?”

Henry pursed his lips and gave a reluctant nod. “Yeah, I guess so. I think he’d be great, but I was talking to Robinson about it this morning, and I didn’t really think about that.”

“It certainly would be a big change,” Osborn agreed. “I myself am nervous about what a promotion beyond first sergeant would mean for Webster.”

“Sir?”

“We’re old friends, you know, and Webster has such a hard time being away from his family. I worry if we aren’t able to bunk up together, he’s going to be lonely.”

Henry considered Osborn for a moment. “It would be lonely if Charley ended up in an officer’s tent.”

“An officer’s tent has its perks, and lots of fellows promote their friends behind them. I wouldn’t worry too much, Schaefer,” Osborn smiled. “That’s a long way off, anyway, and he’d need to get past first sergeant to make it out of the squad. That’s a challenging jump to make, given there’s almost ten fellows to choose from among the sergeants.”

“You’re making a good go of it, though.”

“Thanks.” Osborn gave a small, private smile. It made his face seem younger, somehow. “I’m really heartened that we got this assignment.”

“Yeah,” Henry replied. “Here’s hoping we don’t mess it up.”

⸻

Henry and the rest of the squad returned to camp for supper having found no enemy worse than the mud through which they had to plod their way.6 The camp was buzzing with grumbles.

“What’s going on?” Charley asked Corbett from the Hastings Squad, Henry close on her heels.

“We’ve run out of firewood,” Corbett replied. “After two days camping here and building a damn bridge, turns out we can’t find any more to forage.”

“Couldn’t we fell a few trees?” Henry asked.

“Sure, but it’d be green wood and it would smoke to high heaven, giving away our position,” Corbett replied. “Fellows have been eyeing that split rail fence over yonder, but the damn Big Bugs are fussing that it’s private property.”

“Not this again,” Charley glowered, crossing her arms. “This is such bunk. Why do we hand them this power? Freezing our soldiers will help no one, especially as close as we are to catching up with Zollicoffer.”

“Oh yeah, did you see anything on the advance guard?” Corbett asked, grinning.

“No, nothing but mud,” Henry replied.

“That’s too bad. Would have been nice to finally shoot a Reb instead of treating his property like a goddamned church.”

“This is nonsense,” Charley said, throwing up her hands. “Come on Henry, let’s go talk to Lieutenant Thomas.”

“What?”

Charley grabbed his sleeve and dragged him down the row of tents. “I gotta practice my diplomacy, after all.”

Lieutenant Thomas was hiding in the Company K officer’s tent. It was a large A-frame tent, big enough to stand in. From what Henry had heard, it fit two trundle beds and a table that they lugged from camp to camp in the wagon.

“Oh, how civilized,” Charley sneered as they approached.

“You think Captain Noah’s in there?”

“No, I doubt it. Not if he’s got the measles like everyone says. They’ve got them all quarantined up that hill.” Charley kicked her chin in that direction as she reached out for the tent flap poised to knock. She looked at her hand for a moment, shook her head, and called out, “Lieutenant Thomas? Do you have a moment, sir?”

Lieutenant Thomas peeked his head out between the tent flaps. “If you’re here about the firewood—”

“—I know, sir,” Charley cut in. “I’m sure you’re freezing too—”

Henry doubted that given the smoke puffing out of the tent’s stovepipe.

“—but the men are cold and tired and this rain just won’t stop,” Charley finished graciously. Henry shook his head and looked at her more carefully. He could imagine her asking for church donations. Sort of. She was still in trousers, mind, but he could see that righteousness in her countenance.

“Don’t you think I know that, Private?” Lieutenant Thomas tilted his chin up to give them a lowering look. “Top brass won’t budge on it. Says it’s a matter of propriety.”

“Sir, all due respect, but to hell with propriety,” Charley replied with the relish Henry was more accustomed to hearing. “No one ever won a war for respecting their enemy’s propriety.”

Thomas’s eyes did a movement that suggested he was trying to keep from rolling them. “I’m with you, Private, I am. But my hands are tied.”

“That’s too bad,” Charley said. “Everyone’s rooting for you to get captain if Noah gets furloughed. Woodbury’s a hard case and no one likes him. It’d be better for us all if we had a captain we wanted to fight for.”7

Thomas stared at her a moment. “That’s very flattering. I’ll see what I can do. You’re dismissed.” He disappeared and swished the tent flaps closed.

Charley frowned and turned back toward their tent.

“Is that true about the captaincy?” Henry asked as he caught up to her.

“No,” she replied. “I haven’t heard anyone say two nice words together about Lieutenant Thomas.”

“He could be worse, I suppose.”

“Right. He could be Woodbury. But lots of fellows like being bossed around. Makes ‘em feel wistful for their mothers or something.”

Henry shot her an incredulous look. “Seems like we don’t have much in the way of good options if ol’ Noah has to go on leave.”

“What’s new?” Charley shrugged. “They’ve all got their heads up their asses about something or another.”

“That’s a fine thing to say to get a promotion.” Robinson had caught up with them at the head of their tent row. “Any news on the firewood situation?”

“None. Thomas said he’d see what he could do.”

“Criminy. We’ll be froze half to death by the time he gets all his i’s dotted and t’s crossed,” Robinson said with a shiver. “Come on, get inside and dry off. We’re so close to battle I can taste it. This is no time to get sick.”

Inside the tent, no one worried about anything except sharing blankets and getting warm. Henry sat with Charley between his legs, leaning back on his chest with both their blankets over them as they all complained about the cold and the officers. Despite the fact that he couldn’t hardly feel his fingers or toes, he felt positively serene. He thought a lot about the word comfort and its relative meaning. Was there any condition in which a man must be utterly miserable? At Fort Snelling, they’d complained up and down about the fare when they’d been eating like kings compared to what they had now. The men were over the moon for a scrap of fresh meat, no matter its origin. Perhaps it was man’s nature to be fickle, to long for more when life was abundant, and to thank one’s good fortune when pickings were slim. Hardship sure was exceptional at forcing people to get their priorities straight.8

It was nearly taps by the time word finally got around that they were clear to harvest firewood from the split-rail fence.

“Orders are top rail only, fellas,” Osborn directed as the whole squad hightailed it down the hill. Other squads were on their heels and it was a free-for-all along the fence, squads pulling rails off the top all the way down the line.9

“How are we supposed to know which rail was the top?” Webster asked as they approached the fence.

Henry and Charley already had the rail half-off the fence before they paused. Henry looked down the line. The rails were stacked the same way a log cabin wall would be, zig-zagging across the landscape so that it was held vertical by plodding angles instead of nails or pilings.

“What do you mean? That rail’s the top one,” Williamson said.

“That’s right!” Charley agreed. “Only the top rail, and this one’s on top.” She shoved it toward Henry and he grinned, lifting it off.

Robinson and Hower were bent over laughing while Charley and Henry carried the rail back toward their camp. They’d only gone a few paces when Osborn’s voice rose above the din.

“Hower, come now, we know that one’s not a top rail!”

Hower’s voice was gleeful when he replied, “It is now!”

Henry glanced over his shoulder and saw Hower and Robinson squealing with mischief as they followed, another rail supported between them. Osborn was throwing his hands up while Webster just shrugged. Henry hoped they would just lift a third rail and be done with arbitrary appearances. He knew better though. Besides, just as Osborn was starting after Hower and Robinson, Krüger and Williamson lifted the third rail and scampered off the long way round.

Back at the tent, roll call accounted for, Henry lounged back on his bedroll with a merry fire warming his toes.

“See, I told you that you had the makings of an officer,” Henry murmured to Charley, who was curled up next to him.

“You know, some men see danger and they fight, others flee, but I forgot how effective fawning can be,” Charley replied, voice quiet in his ear. “I guess there’s still a bit of use for my feminine wiles.”

“Don’t talk to me about your wiles,” Henry intoned. The squad was hunkering down for sleep, and Charley and Henry weren’t the only ones snuggling up together. Robinson was kicking Hower for hogging their blankets, while Krüger had Williamson tucked under his chin like a child with a doll. Webster was reading a few lines aloud from his Bible with Osborn curled on his chest. Henry had his arm around Charley and the fellows were all still awake. No one batted an eye. Henry supposed he wouldn’t have either, if he hadn’t had Charley. He wasn’t sure whether it was her sex or whether he was in love with her that made him self-conscious of any outward appearance of intimacy, but it was clear neither would be revealed if they shared their bedroll. God, a man could get used to this kind of freedom.

“It was a long day,” Henry yawned.

“A long couple of days,” Charley replied, catching the yawn too. “We built a bridge.”

“A temporary bridge.”

“A real bridge. With trusses.”

“Next time, we’ll add turrets.”

“We’ll make a whole drawbridge.”

Henry smiled, but it felt a little hard to get his whole face behind it. Battle was bearing down on them. In a matter of days, they’d gain their enemy. The faceless enemy who had been dogging his dreams for months. Perhaps all of this jockeying for power and position was fruitless in the face of what inevitably was to come. Maybe this time next week, he’d look back on himself with shame for his naivete, his privilege. Perhaps these conditions they were under now, which were the most austere they’d experienced, would seem like luxury in the face of what was yet to come. He couldn’t worry about that now. Battle would change him, that was sure. He longed for it, in a strange duplicity of excitement to finally do something of consequence and a dread that made him just want to get it over with already.

He looked down at Charley. She was curled into his side, her cheek nestled in the dip between his shoulder and chest. Her hair was tumbled over her brow and her eyes were closed, dark lashes sweeping her cheeks. God, but he loved her. He felt such relief knowing that, almost as much as he felt knowing that Robinson and the others weren’t batting an eye every time he touched Charley. That perhaps they had greater liberty than they realized. In many ways, despite the cold and the sparse rations and the mud, he didn’t want this march to end.

⸻

XXII

Outside Columbia, Kentucky

Sunday, January 12, 1862

“YOU know what I have a newfound gratitude for?”

Charley looked up and caught a faceful of cold rain. “Ugh, what?”

“Roads,” Henry replied with a huff of effort. “Paved roads. With cobblestones, or pea gravel. Flagstones, even if they have a little moss growing between them.”10

“I suppose I never expected to wax poetical about road surfaces,” Charley replied, tucking her face down again so that the brim of her forage cap caught the blowing sheets of rain. “But I must admit I’m enamored with the notion.”

Robinson gave a shrill laugh.

“Bricks,” Henry continued. “Strong, well-baked bricks, tightly packed.” His voice tightened as he started to slide in the mud, and he reached out for Charley’s shoulder to steady himself. She put a hand on his waist and guided him upright with a fistful of his greatcoat.

“Wood block pavement,” Henry intoned, and his voice was positively erotic.

“Stop, I can’t bear the longing,” Charley replied, and it was true, both in terms of the paved roads and in terms of what she wanted to do to him when he used that voice.

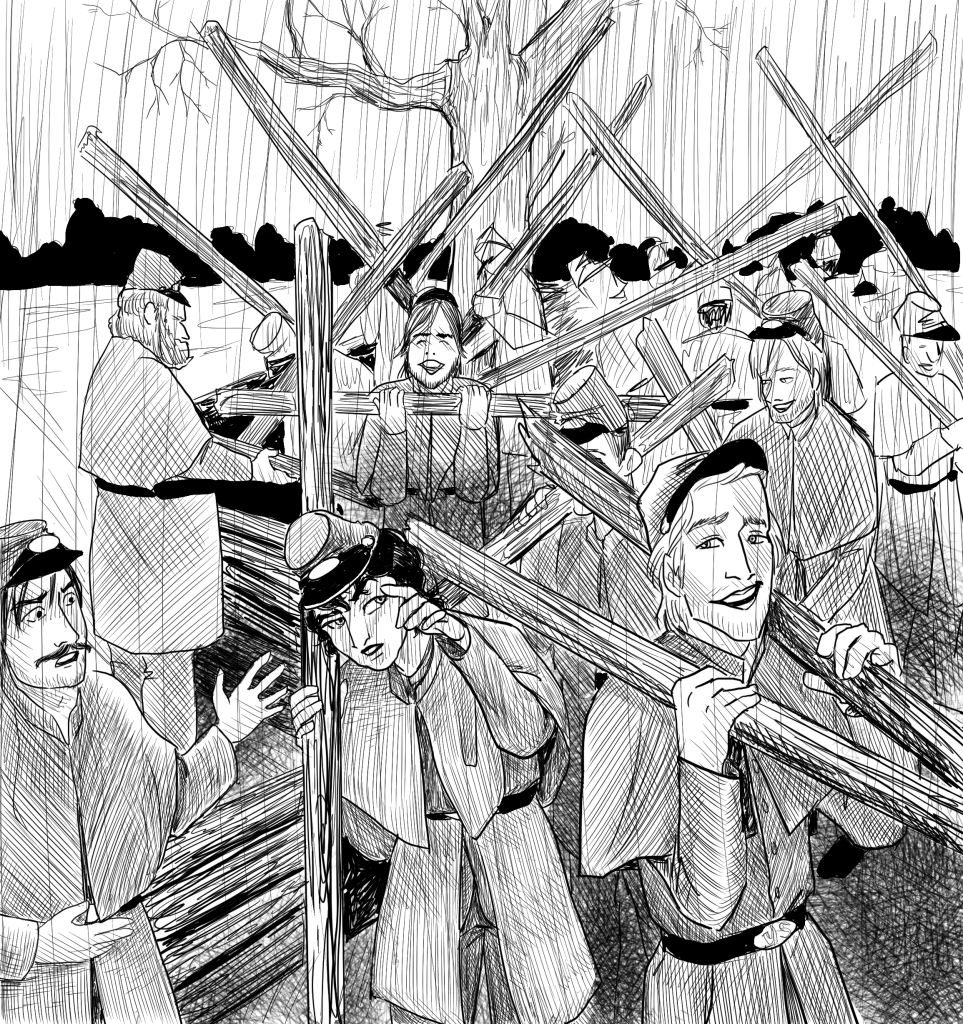

They’d been marching all morning, through the relentlessly terrible weather. They’d only managed nine miles the day before, and ended up waiting for hours in the elements for the wagons to come up, pitching tents and cooking supper long after dark. Even after loitering in the freezing rain for hours, no one complained because they could have ended up gnawing hardtack under the shelter of their cannons with the artillerymen, whose wagons never arrived at all.11 Charley’s mind spun for those hours spent waiting, trying to figure out a better solution to the wagon problem. Supplies were imperative to a healthy army. Given the number of men falling to disease—measles was still running rampant, especially among the Kentucky regiment that had been battalioned with them—the present system was inherently flawed. The enemy could cut them off easily from behind. It seemed to Charley that the only solution was to carry a greater burden of the supplies with the men.

That, or march a shorter distance so they didn’t leave the wagons too far behind.

“Goddamn this damned cursed creek!” It was Hower’s voice ahead of them. Charley looked up and caught another faceful of rain. Henry’s shoulders fell despondently.12

“Again? We just crossed it not thirty minutes ago,” Robinson whined.

“I don’t think I’ve ever seen a creek that winds so much,” Williamson added. “And I’ve been up the Rum River all the way to Mille Lacs.”13

“Ah, come on,” Henry said. “My boots just stopped sopping from the last time.”

“That can’t possibly be true,” Charley replied, even as she took up his elbow to raise both his shoulders and his spirits. “Maybe our boots are so packed with mud now, it’ll serve like a sort of waterproofing.”

“Or, the creek will wash the mud away,” Henry countered. “Which, now that I think about it, doesn’t really serve any great purpose, but I hate this mud more than I’ve ever hated anything in my whole life and it would give me satisfaction to see it dashed on the rocks.”

“We must take our solace where we can.” Charley squeezed his arm with deeper affection than she’d previously dared. The nasty weather, the slog of the march, and the uncertainty of battle lurking over every hillock made previous fears seem frivolous in comparison. Besides, as Henry had pointed out astutely yesterday, the men writ large paid utterly no notice to scarcely any of the affection they increasingly dared to express. In fact, they seemed to expect it. At one point over coffee the previous day, Robinson had made a jibe at them about being an old married couple, and the squad had laughed. Only Krüger had rolled his eyes, and he’d been doing that for months now with no consequences.

It was all too good to be true. Charley watched water drip down the end of Henry’s nose and couldn’t help but imagine it as blood. The closer they got to battle, the more intrusive these thoughts became. He was so good, so captivating and pure, and he loved her. It was only a matter of time before he was snatched away. They were at war for God’s sake. If battle didn’t take him, he’d eventually tire of her and find a woman more suited to the roles of wife and mother. Besides, she couldn’t ever have the assurances of marriage with him. No matter how much time passed, that would still hover over her.

She let the icy water of the creek shock these thoughts from her mind as they trod across it for the umpteenth time. The wagons were going to struggle with this crossing. It was rocky and uneven, and the swell of the creek after days of rain had eroded the banks to a sharp drop almost a foot deep. She allowed her thoughts to spin strategy of how the teamsters might remedy this most efficiently, not because it would do any good at all, but because it was preferable to worrying about the future.

It was dinner time when the ranks slowed to a stop. Charley could tell not because of the position of the sun in the sky, which was entirely unknowable behind the heavy, low clouds spitting rain upon them, but from the grumble of her belly.

“How far have we gone?” Charley asked Hower as the ranks oozed out of the woods and into a clearing, the mud slopping less as the men covered a wider ground and the grass tamped down in a layer of protection.

“I’d reckon about eight miles,” Hower said, squinting up at the sky like it could tell him anything about how long they’d been marching. “Not as far as yesterday.”

“Hm.” Charley sloughed rain from her face with her hands as the squad fell into ranks on the latest makeshift parade ground. From behind her, a hand snaked around and pinched her nose. She reeled and smacked the hand away, spinning on her heels. “What the Sam Hill—”

Henry blinked at her placidly. “Your nose looked cold.” He was barely holding in a crooked grin.

Charley’s mouth pinched and she refused—she positively refused—to let anyone see the affection purring in her chest. “That’s not any of your—”

“—Is your nose cold?”

“Shut up, Schaefer, you’re not—”

“—Is it?”

She scowled. “Yes, but—”

Henry reached out and put his fingers over her nose. It was a gentle gesture, but she shook her head sharply away. His hand chased her and after a moment, she found herself grappling his arms as he laughed and she dodged and the boys all howled with laughter.

“Why won’t you let me—oof—help you?” Henry laughed as Charley twisted away from him. He held onto her with both arms.

“I don’t need your help!” Charley insisted and tried to hold the laugh out of her voice.

“Your nose is going to fall off,” Henry said and pulled her back into his chest with his damnable gymnasticks strength.

“It is not, you’re being ridiculous. Stop this at once.” Charley’s voice went tinny as Henry’s cold wet hand went over her nose again. His other hand held her by the waist, and she stopped bothering to struggle against him. Her voice was honky when she said, “There. Are you happy now?”

“Incandescently,” Henry murmured into her ear. His hand was cold. Objectively, it should have helped not at all. But his closeness, his dearness, raised the flush in her cheeks and it did warm her, from her toes to her nose. Of all the damned silly things to do…

“In ranks, soldiers,” Osborn reminded, but he was grinning too. They were all laughing at Charley’s expense, except it didn’t feel like that at all. It felt comfortable, almost familial. Like how Charley imagined a fine party full of friends would be, laughing and ribbing each other in casual affection. It was something she’d only ever observed from outside before. Nothing she’d ever felt included in. Perhaps Henry’s embrace wasn’t the only thing warming her from the inside.

“Yeah, Schaefer, in ranks,” Charley said, shrugging him off and trying not to smile.

Lieutenant Thomas called the ranks to attention, and the whole squad straightened up and assumed the position of the soldier.

“Soldiers, we will stop here for the day and wait for the wagons to come up,” Lieutenant Thomas announced. “There are a few structures on this clearing, but as you well know, Command will not stand for the disturbance of private property. We’re here to fight a war for honor and fidelity and respect. We’re not looters. As such, Captain Bishop has ordered his company to stand guard on all the outbuildings.”

Charley’s lip curled slightly as her eyebrow rose. Sure. She glanced at her comrades. Hower was leaning around Osborn and mouthing something at her with waggling brows. Charley frowned and shrugged. She couldn’t understand what he was trying to convey. It didn’t matter anyway, because Osborn quickly noticed him and reached over to pinch him in the arm. Hower yelped back into position and stayed that way until they were instructed to fall out.

When they were dismissed, most squads made for the scant cover of the trees that lined the clearing. Charley’s squad huddled together under some pine boughs, which brought more reprieve than most of the desolate winter branches. All except Osborn, who was called away by Lieutenant Thomas for some mundane task he was more than happy to perform if it meant more recognition in anticipation of a promotion. Hower was positively shaking with news as soon as they all made it under the boughs.

“It’s a still,” Hower gasped when he had their attention. “The private property. An applejack still, and it’s loaded with barrels of the final product.”14

Eyes rounded across the squad.

“But Command has instructed us not to disrupt private property,” Webster reminded.

“Command also told us to only take the top rail,” Charley couldn’t help but reply, “and we saw how well that turned out.”

“Well, we knew what they meant, didn’t we?” Webster said, exasperated.

“We did, but it wasn’t enough,” Charley retorted. “Men who are well-provided for don’t have any need to loot.”

“I’m not sure that’s true—” Webster started.

“Regardless, we certainly haven’t had an easy time of it. We’re not complaining—you don’t see any of us complaining—”

“I think I see you complaining right now.”

“I’m not complaining. I’m arguing.”

“Ah, so that’s why this feels so exhausting.”

“Webster, that’s not the point I’m trying to make.”

“Yeah,” Hower put in. “The point he’s trying to make is that we’ve worked damn hard and put up with a whole lot and if anyone deserves a goddamned drink, it’s us.”

Webster threw up his hands. “What if the enemy bears down upon us, and we’re all sodden beyond comprehension?!”

“We’re already sodden,” Charley muttered. The boys all laughed. Webster glared at her. “Sorry, but we’re expected to take a whole lot, sir, without complaint. We’re not good soldiers if we fuss, but Command can carry on making slapdash decisions and blaming the weather for their incompetence, then calling us selfish and weak for wanting basic creature comfort like wood for our fire. Fellows are catching the ague left, right, and center, and it’s preventable. We don’t have to go on living like animals and calling it living like men. But heaven forbid anyone point that out. If they wanted praise, they could show us what it looks like.”

The boys all nodded. Webster sighed. Hower gave her an approving pat on the shoulder.

“I for one walked through ice water six times today,” Hower declared. “And I guarantee you the Hastings boys are already tapping one of those barrels. If I can’t warm myself by a fire under an actual shelter, I’m damn well going to warm myself with applejack.”

Hower turned on his heel and made for the clearing. It didn’t take the boys much time at all to decide which corporal to follow. Charley looked up at Webster for a moment and shrugged. She might have wrecked all the goodwill she’d built with him while on advance guard, but she knew that he knew she was right. If he was so petty as to pass up good sense for loyalty, then he was just as bad as the rest of the big bugs.

“Charley, you coming?” Henry was hovering outside of the pine boughs.

“Yeah,” Charley said. “Webster, how about you?”

Webster sighed so hard he slumped back against the tree trunk. “I don’t know why I even try to hold the line with you all.”

“It was a very valiant attempt,” Charley comforted. “So valiant, in fact, that you deserve a drink.”

Webster’s faced cracked a smile.

“See, doesn’t it feel good to have your effort recognized?”

Webster rolled his eyes and straightened, following Charley and Henry out into the clearing. “Criminy, Smith, do you ever just let anything go?”

“I’ve been asking that question for months now,” Henry laughed.

Charley grinned. “No. Never.”

⸻

Footnotes

- “Romantic Friendship” by E. Anthony Rotundo, 1989. In the mid-19th century, romantic friendships among people of the same sex were fairly common. Same sex intimate friendships are well-documented in Rotundo’s article, and were not unusual among young men and women of all ages. Some of them were sexual, but most often, they were emotionally romantic relationships. “This special form of friendship evoked no apologies and elicited no condemnations; apparently, it was accepted without question among middle-class male youth.” ↩︎

- Camp followers were most often women married to officers or other enlisted men, performing duties like laundry or other tasks needed to support the troops. There are recorded examples of public women following troops, but this was actively fought against by commissioned officers (which may be why camp followers were all sent home in Lebanon). Lowry, Thomas P. The Story the Soldiers Wouldn’t Tell: Sex in the Civil War. Stackpole Books: Mechanicsburg, 1994; Giesberg, Judith. Sex and the Civil War. The University of North Carolina Press: Chapel Hill, 2017. ↩︎

- I made this up. I have no idea if Woodbury was a hardass, but I do know that he was specifically in charge of drills. I extrapolated the archetype of hardass drill sergeant from there. ↩︎

- The squad selected to do this on January 10 was actually Sergeant James B. McDonough’s, and William Bircher was a member of his squad. Bircher, William. A Drummer-boy’s Diary: Comprising Four Years of Service with the Second Regiment Minnesota Veteran Volunteers, 1861 to 1865. United States, St. Paul Book and Stationery Company, 1889. Page 10. ↩︎

- Referencing ‘Die Lorelei’ by Heinrich Heine, 1824. ↩︎

- Bircher. Sounds like the advance guard didn’t actually return to the camp in his account, but waited for the rest of the battalion to catch up instead. I made a different choice, because I had top rail hilarity to pursue. ↩︎

- I have no idea if Woodbury was a hard case! I made that up and he’s a real guy and I clearly feel weird about it. ↩︎

- Reflections adapted from Bircher. ↩︎

- Bishop, Judson Wade and Family Papers. Minnesota Historical Society, Manuscripts P1922 Box 1 vol. 1-2. ↩︎

- I am so delighted that this website exists. ↩︎

- Bircher, 10. ↩︎

- “Came 8 miles. Roads outrageously muddy. Crossed creek many times during the day. And camped within 20 miles of Rebel Zollicoffer.” Thomas Fitch Diary. Minnesota Historical Society, Manuscripts, P961. ↩︎

- Wakaƞ Wakpa, translating to Spirit River, was the Dakota name of this switchback river that connects Lake Mille Lacs, aka Mde Wakaƞ (Spirit Lake) to the Mississippi River, aka Wakpa Taƞka. In 1767, Jonathan Carver mistranslated the Dakota name to Rum River and we really should probably restore the Dakota name, since it’s objectively less drunk-sounding, but then we’d have to change all the road signs, and Highway 169 really does cross the river an awful lot. The Ojibwe name also makes more sense, because it’s Misi-zaaga’igani-ziibi, which means Great Lake River, and is derived from the name of Misi-zaaga’iganiing, Lake Mille Lacs, which is the river’s source. Did I give Williamson this line just so I could write this footnote? Maaayyybe… ↩︎

- “We encamped about noon near an old time ‘apple jack’ still. It had recently been in operation and a considerable quantity of the seductive product thereof was yet in the rude building. This was speedily appropriated by the soldiers as ‘contraband of war,’ and a night of uncommon hilarity in the camps resulted.” Bishop, Judson Wade. The Story of a Regiment: Being a Narrative of the Service of the Second Regiment, Minnesota Veteran Volunteer Infantry, in the Civil War of 1861-1865. United States, Published for the Surviving Members of the Regiment, 1890. ↩︎

⸻

Copyright 2025

All rights reserved. This is a work of fiction. Unless otherwise indicated, all the names, characters, businesses, places, events and incidents in this book are either the product of the author’s imagination or used in a fictitious manner. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or actual events is purely coincidental.

Printed copies permitted for individual personal use only. Duplication and/or distribution of this material, in print or digital, is strictly prohibited. Any fair use duplication of this material should be credited to the author.

Any use of this work to “train” generative Artificial Intelligence technologies is strictly prohibited. Be a part of celebrating and protecting the intellectual property of authentic human creators. Creation isn’t just about the product; it’s about the process. We lose much more in skills, processing, and practice than we gain when using AI technologies as a short-cut.